Revolutions Per Minute will feature new and existing works by 30 Chinese sound artists, including Wang Changcun, Xu Cheng (a member of the renowned Shanghai noise group Torturing Nurse), Yan Jun, and Samson Young. Wang Changcun, Xu Cheng, Samson Young, Qu Qianwen, and Xie Zhongqi will be in residence at Colgate throughout the duration of the exhibition. Along with the exhibition’s curators Wenhua Shi and Dajuin Yao, these artists-in-residence will present live sound art performances during the opening week of the exhibition, including improvisations, inter-media performances, and circuit bending. They will also conduct demonstrations on sound art workshops throughout the course of the exhibition.

Tuesday, March 26, 6:00 pm--Opening remarks by Dajuin YAO with Reception

Little Hall

Friday, April 26, HAMILTON SOUND LIBRARY, Village, Hamilton, NY

TOPIC 1: Wednesday, March27 9:20am - 11:10am, Samson YOUNG: Brainwave Composition, Hamilton Library, 13Broad St., Hamilton

TOPIC 2: Wednesday, March 27 12:20am -2:10pm, Dajuin YAO: Real-time Audio-Visual Performance, 208 Little Hall, Colgate University

TOPIC 3: Wednesday, March 27 4:30pm -6:30pm, Dajuin YAO: Phonography: The Art of Field Recording, 208 Little Hall, Colgate University

TOPIC 4: Thursday, March 28 9:20am -11:10am, WANG Changcun: Max/MSP Improvisation, 208 Little Hall, Colgate University

TOPIC 5: Thursday, March 28 1:20pm -3:10pm, XU Cheng: Electronic Circuit-Bending and Effect Boxe Building, 208 Little Hall, Colgate University

Wednesday, March 27, Performance, Hall of Presidents, 2nd floor, James C. Colgate Student Union, 7pm

QU Qianwen, XU Cheng, XIE Zhongqi & Samson YOUNG

Thursday, March 28, Performance, Ho Tung Visualization Lab, Robert H.N. Ho Science Center, 7PM & 9PM

Dajuin YAO, WANG Changcun, Wenhua SHI & QU Qianwen

Friday, March 29, Golden Auditorium, Panel Discussion: Christoph COX, Samson YOUNG, Dajuin YAO & Wenhua SHI.

Little HAll, PERSSON HALL, JB COLGATE HALL & DANA ART CENTER

Monday - Friday, 10:30AM - 4:30PM, Saturday & Sunday, 1PM - 9PM

MAD art Gallery, Hamilton

Monday - Friday 4PM - 6PM, Saturday 9AM - 12PM

China Pavillion & Hong Kong Pavillion, Village, Hamilton

Monday - Sunday, 9AM - 9PM

HO Science Rock Garden

Sunday - Friday, 7AM - 9PM

Bridge Listening Beijing

Monday - Thursday, 4:30PM - 9:30PM & 4:30PM Friday - SUNDAY 9:30PM

JAMES C. MCKINLEY JR. NEW YORK TIMES

Wang Changcun

Audio-visual Performance

Vvzela QU

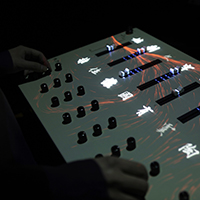

"Scape-Sequencer" (2010)

"Scape-Sequencer" (2010) is an audio-visual work for live performance. It takes everyday sensory experiences in the city of Shanghai as its source material which is then remixed and synthesized with software programming and hardware controllers into a brand-new audio-visual experience.

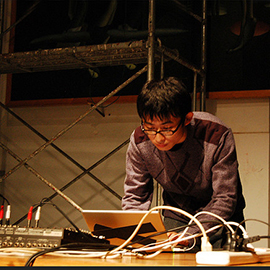

Cheng XU

Born 1980 in Shanghai, China. Since 1999, Cheng has worked with different styles of sound and music, including concrete music, plunderphonics, electroacoustic, harsh noise, ambient, and improvisation. In 2003, his works were selected in the first survey anthology of Chinese sound art "China - the Sonic Avant-Garde" (Post-Concrete). In 2005, Cheng formed the NOIShanghai group with noise artist Junky to promote experimental music, which has since organized over 40 performances by sound artists and noise artist from around the world. In the same year, Cheng joined the world renowned noise group "Torturing Nurse," which has presented over 100 performances and 200 releases. In 2010, Cheng joined the free improv group, "Free Music Collective of Shanghai."

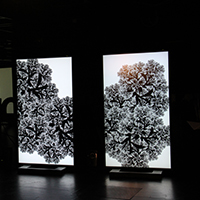

Installation: Liquid Borders

Installation: Beethoven Piano Sonata No.1 -14 (Senza Misura)

Performance: I'm thinking in a room, different from the one you are hearing in now

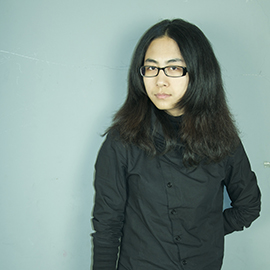

Samson Young

(b.1979) – composer, sound artist and media artist. Received training in computer music and composition at Princeton University under the supervision of computer music pioneer Paul Lansky. Currently an assistant professor in sonic art and physical computing at the School of Creative Media, City University of Hong Kong. Principle investigator at the Laboratory for Ubiquitous Musical Expression (L.U.M.E), and artistic director of experimental sound advocacy organization Contemporary Musiking.

In 2007, he became the first from Hong Kong to receive the Bloomberg Emerging Artist Award for his audio-visual project “The Happiest Hour.” In 2009, CNN’s global portal CNNgo named him one of the top “20 people to watch in Hong Kong.” His brainwave non-performance “I am thinking in a room, different from the one you are hearing in now” received a Jury Selection award at the Japan Media Art Festival, and an honorary mention at the digital music and sound art category of Prix Ars Electronica. He was Hong Kong Sinfonietta‘s artist associate in the 2008/09 season, an organization for whom he had created a number of multimedia music productions.

Listening Station: ddddoottt

Listening Station: Breathe

Sound Performance: Archival Listening

Xie Zhongqi 謝仲其

Xie Zhongqi is a sound artist, computer music composer, and translator. He is the member of Taipei Sound Unit. He was the assistant of Computer Music Lab in Center for Art and Technology (Taipei National University of the Arts.) He received the honorable mention awards in BIAS Sound Art Exhibition and Sound Art Prize in the Digital Art Awards Taipei. His thesis was selected in Digital Art Criticism Awards. Aside from long devotion in sound arts and technology arts, he was also a columnist in DoMyouBan anime/manga culture magazine. He had written and translated several reports and interviews of Japanese anime/manga industries, which are the rare introductions in Chinese language.BBuilt into the title of this first survey exhibition of sound art in China is obviously a pun – "RPM" being a measure with which we describe the different speeds of a record turntable and different types of record formats, but it also refers to the revolutionary nature of the modern Chinese society, and how unbelievably fast a pace it is changing at.

As far as the auditory tradition in China is concerned, the Cultural Revolution achieved its goal with total success, cutting newer generations off from most musical forms, Western as well as Chinese. For the young people growing up in the 1990s and early 2000s, Western-influenced pop, rock, and punk were the only musical nutrients and formed their collective aural memory. In the area of experimental sound, the Chinese artists had a blank slate to start over with.

TThe year 2003 was a landmark for sound in China. "China: the Sonic Avant-Garde," produced by and released on Post-Concrete in the U.S., was the first comprehensive compilation CD introducing Chinese experimental sound works to the world. Later in the same year, Post-Concrete produced "Sounding Beijing," the first international sound and media art festival in China, a historic event that gathered together Western and Chinese artist, and a hardcore audience from all over the country under one roof. The two events were a declaration of a maturing experimental sound art scene in China, the existence of which even the practicing artists themselves did not fully realize at the time.

Today, ten years later, we can find Chinese artists working in a wide range of sound genres: extreme noise, musique concrete, electroacoustic, field recording, mixer feedback, circuit-bending, interactive controller, live audio-visual, glitch, minimal electro, gallery-based sound art, free improvisation, etc.

Yet, a simplistic "We've got (fill in genre name here) in China too!" is not our concern here. This essay will focus on and map out significant emerging tendencies and directions unique to Chinese sound art practices.

In a 2004 essay, underground rock critic, producer, and soon sound artist Yan Jun summarizes the main characteristic of the new sound in China as "re-inventing" [the wheel] – "which means to intentionally or unintentionally re-invent techniques or rules that have already been invented by others, thus producing an effect that does not exist in the original context, that both destructs and rebuilds the original system."

What Yan terms "reinventing" is only natural for a culture cut off from the rest of the world and needs to rebuild. But, the real problem for China was that it was in fact a process of "building" from nothing, not "re-building," since not only did China lack a tradition of modern/contemporary music (which is crucial for the development of "sound art," even in the West), but also a link to its very own sound heritage.

Now, under today's "we-have-everything" surface of experimental sound in China, the energy and diversity of which have been much appreciated recently in the West by critics, magazine editors, and audiences, something is a bit anachronistic, or out of context, with the global progress (such is the case with the current prominence of free improv, and harsh noise in China).

This straight jump to the avant-garde skipping the modernist phase might prove to be dangerous long term, but it's the same with many other aspects of this society. Besides, this might give it a special character, instead of being a simple cloning of what's outside. (More on the cloning culture later.)

Chinese experimental sound started to blossom in the age of Internet (not just personal computers), and this has everything to do with its structure. The sudden opening up and importing all styles anachronistically, where all foreign works of any genre are accessible via net download, and at zero cost, decontextualize all genres and trends, resulting in a different mentality towards everything heard, and seen.

In the early years, it was contemporary visual artists, with their curatorial connections and established visibility in the art circle, who first made attempts at "sound art" that fit the narrow definition of the term currently used in the West today (i.e., sound installations that can be shown in a gallery, can be described with text, etc.). However, sound in such works was more or less a crude byproduct and the works were side projects for these artists themselves. They never amassed enough energy to create a body of work or their own aesthetics of sound.

In 2001, well-known contemporary artist Qiu Zhijie gave a solo sound art exhibition in Japan, titled "Sound of Sound." Curiously, all the three works in that exhibition were silent. Nevertheless, they do refer to the sound in Chinese tradition in various ways through writing and language, though silently.

Visual artists attempting to use sound are often baffled at what they really want to do. Lack of understanding of the medium, its history, and, most importantly, the culture of listening, Chinese or non-Chinese, prevent them from moving forward. It was not until the experimental sound practitioners entered this territory that the works started to have both the materiality of sound and the spatiality of form fusing together in a satisfactory manner.

The "Buddha Machine" (2005) by electronica duo FM3 (Christian Virant and Zhang Jian) is a major success, though an exceptional case. It uses cheap, mass-produced small Buddhist prayer machines and replaces the chanting with FM3's own electronic ambient clips. The success is not only in the concept, but more in making the product marketable to the world. The "Buddha Machine" can also be seen as a tongue-in-cheek look at mass production culture and superficial religiousness rampant in China now.

Samson Young's "I am thinking in a room, different from the one you are hearing in now" (2011) is a performance/installation piece that uses the performers' brain wave to control a sound-making device. Unlike other such experiments in interactive technique, this work shows its depth in knowledge of and linking to the tradition of sound art, as an homage to sound art pioneer Alvin Lucier and his brain wave and room acoustic milestone pieces. It is significant to note that this work comes from Hong Kong, where, like Taiwan, the Western sound art history is better known, and works from these two regions fit more snugly into the so-called "sound art" category.

Phonography artist Sun Wei's "Song for 100 Children" (2006) is an installation that can also be presented as a performance. The work features two Chinese printing machines, to which are fed a text of the lyrics of this Sichuan folk song. The sound of printing is picked up, amplified and then modulated by computer. The resulting output is a spectacular, psychedelic sound mass despite its "traditional" source input.

Yan Jun's “How To Eat Sunflower Seeds” (2011-13) is a quadraphonic installation playing back the sound of four persons cracking sunflower seeds (a popular Chinese snack and pastime) as if in a conversation. This relaxed and unambitious work is typically Yan Jun's style of making art out of everyday life. His other work "Still Life, Wild Life" (2013) sets up a telescope in front of a window, through which the spectator can watch a video of someone setting off a firecracker in different ways playing on a monitor outside, and at the same time hear the sound through headphones.

Young sound artist Weng Wei's "Twice-Cooked Pork" (2012) is a unique combination of an interactive sound device and video projection. The title (the famous Chinese dish from Sichuan) refers to a cross-modulation between ancient calligraphy (video projected onto the controller) and the sound of ancient Chinese phonetics, which the audience can control in realtime through moving sliders. The technique behind the work is cutting-edge and complicated, involving Max/MSP/Jitter, Arduino, Processing, as well as hardware design.

The use or reference to traditional or contemporary Chinese culture can be seen in most of the works mentioned above, even Yan Jun's seemingly casual seeds cracking and firecracker ignitions are inescapably Chinese.

One work that integrates ancient culture successfully is Jiang Zhuyun's "Sound Medicine Chest" (2007). 81 sound samples categorized into machine, human body, fire, wind, and water are stored in an old Chinese medicine chest, the kind used in old-time pharmacies. By opening a combination of different drawers, the audience can hear different sounds played back from a medicine boiler pot, as if taking different prescription medicine. The healing power of sound, traditional Chinese medicine, phonography, digital signal processing, interactive installation are all perfectly united in this monumental work.

Dajuin Yao's "Geophone Nanking" (2005) is a rare case of referencing the mysterious and fascinating ancient Chinese auditory heritage. The sound installation employs the analogy of a "geophone" (diting in Chinese, "earth listening"). It is a military surveillance device the Chinese used in battles 2000 years ago, where a large pottery urn is buried underground and a scout is placed inside to listen for the attacking enemy's tunnel digging; the physical principle behind this device is known in the West as "Helmholtz resonance." In the gallery, "Geophone Nanking" is set up as a large black box in which the audience can sit in total darkness and listen to a surround-sound collage of field recordings made in Nanking. This site-specific work is an homage to the war-ridden city of Nanking in sound, and in concept.

To say that China lacks a "sound art" tradition is in fact misleading. For sure, "sound art" in its contemporary Western definition did not exist in China, but the culture had the most advanced sound theory and auditory aesthetics among world cultures. Ancient text such as Yue Ji ("The Book of Music", ca. 10 B.C.) and Ji Kang's "Treatise on the Non-Emotive Nature of Sound" (ca. A.D. 260) are invaluable texts in aesthetics, and have been the foundation of Chinese musical aesthetics for two thousand years. (For example, see sound artist Samson Young's essay "Decay, Resonance, Auditory Space: Sonic Materiality and Culture.") Not to mention equal temperament, the well-tempered scale, the invention and publication of which by the Chinese Prince Zhu Zaiyu predated its discovery in Europe. (See Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, Vol IV:1.)

There are numerous acoustic inventions and examples of intriguing acoustic phenomena throughout Chinese history. One ancient architectural construction worthy of examination from today's sound art point of view is the "Echo Wall" at the Temple of Heaven in Beijing. It is a circular wall 200 feet in diameter, to which one can whisper or talk and the sound can be heard by someone on the diametrically opposite side of the circle. But is "Echo Wall" a work of sound art? Well, it would be if it were built today, not in A.D. 1530.

Sadly, this rich heritage of ancient listening culture is unknown even to most scholars and virtually untapped by contemporary sound artists.

Phonography (the art of sound recording, formerly called "field recording," a term that is misleading regarding the types of sound that can be recorded) is one of the areas where Chinese sound art really shines, perhaps unlike anywhere else in the world. On a certain level, phonography might have taken the position of documentary film in China.

With the wider affordability of portable recorders with decent stereo sound, not to mention the unexplored potential of iPhone (which is hugely popular in China) as a recording device, phonography is now a widely practiced genre of acoustic art. But the popularity of phonography in China might have little to do with a love for realist documentary or interest in "sound art"; it's more about a pure fascination with sound, an aspect of real life which also provides maximum aural, emotional, and intellectual satisfaction.

The bizarre reality of contemporary China is simply too powerful to ignore, same with its sound. These sounds from real life are often much more intriguing than any noise generating gadgets, software, or installations in a gallery white box. It is certainly aural voyeurism, a peek into a world not found in Western sound works, even Western phonographic works.

This interest in phonography is significant, for it shows a return to the production, repetition, and dissemination of the Schaefferian sound object, a return to sound itself, and most importantly, to listening itself – the core of sound art, and what most gallery-oriented sound art works tend to lead us away from.

Since 1997, China Sound Unit, a mobile phonography group founded by Dajuin Yao, has focused on non-invasive observation, surveillance, documentation and re-contextualization of the Chinese sonic phenomena. From the very beginning, China Sound Unit has insisted upon a humanistic direction, recording all sounds related to humans, and has shown no interest in natural environment, the animal world, or in mechanical sounds, which is in direct opposition to the contemporary practice in Western phonography.

Many phonographers share this humanistic view in attitude, including those who are not members of the China Sound Unit. An example is the super active PlayBack Unit (Zhong Minjie and Li Zhiying), which operates around the city of Canton and documents the acoustic environments there extensively, once even posing as customer in a "massage parlor" wearing concealed recording devices. Besides releasing CDs and playing live, PlayBack Unit, from 2007 to 2009, set up a blog to post new recordings together with pictures of the sites recorded.( sjp.blogbus.com )

This strong interest in human-related sound phenomena might be considered a defining trait of Chinese phonography. In a way, this tendency can be seen as Confucian, because of the similar emphasis on the world of human affairs, on human relationship.

Together with this emphasis on humanism comes the fascination with the human voice, and language. From a practical point of view, when recording in cities in China, it is difficult to differentiate the location by urban acoustic environments alone, since most cities look alike and sound alike. In Chinese cities, one cannot find "soundmarks," as soundscape theorist R. Murray Schafer calls the sonic landmarks of a site. It is the language, with its dozens of dialects (many of which are mutually unintelligible) and accents, that tell them apart. More over, Chinese culture is above all a culture of text, writing, and literature. Language has always been the core of Chinese history.

And acoustically speaking, for artists using language as sound samples for signal processing, the Chinese language, being tonal (words often share the same sound and are differentiable only through pitch variations) and with so many dialects and regional variations, offers a tremendously rich resource for all types of experimentation in digital signal processing and modulation.

Dajuin Yao has been working with Chinese language processing since 1994, with key works documented in "Dream Reverberations" (1996) and "Cinnabar Red Drizzle" (1999), in which algorithmic poetry, ancient text, granular synthesis and other digital signal processing methods are combined to reveal an unknown acoustic microcosm within the common spoken language.

This enthusiasm for language even extends to Chinese artists working outside the homeland. Wenhua Shi's "What's in Your Suitcase?" uses voice narratives to integrate sound, memory, traveling, and user participation into an interactive sound installation that is fun for the audience to play with.

Works featuring the human voice can be found in two major compilations. "Oral Works" (Kwanyin, 2010), a project initiated by Hong Qile and Yan Jun, is a collection of works showcasing extended voice techniques. "Talk Talk Talk" (to be released on Post-Concrete), on the other hand, is a massive collection of "Chinese speech art," unaltered speech recordings by over a dozen artists and photographers found in all kinds of unimaginable, real-life contexts that are amazing, even shocking, to listen to.

Contrary to Western expectations, the political element is rarely found in sound art in China. And the reading of the Chinese harsh noise scene as critical protest would prove to be too simplistic and naive. The artists in general are not overly interested in politics, and even for those who are, sound art would not be their channel of expression. It's not so much the overall climate of censorship as a shared sense of futility and apathy in the post-1989 era.

And, is there censorship for sound, experimental music, sound art? The disappointing fact is, as long as there are no words or lyrics involved, sound is harmless to the state. That is why extreme noise acts are not censored, even when Torturing Nurse performed in Shanghai, in 2007, with nude in bondage and hot wax dripping. With Chinese urban centers being huge, high-volume noise generators in themselves, such small events in tiny venues can hardly raise an eyebrow.

When asked, some noise artists might claim their art to be political. Even if so, it is more of a theoretical stance than any direct criticism. Harsh noise is for sure underground, subculture, and its anger would more likely be directed towards the urban yuppie society and the era as a whole.

Genuinely and explicitly political works often come from Hong Kong and Taiwan. Samson Young's 2012 work "Liquid Border" (Chinese title "Violence Border") uses contact microphones to record barrier fences in the forbidden zones along the border between Hong Kong and Mainland China.

Edwin Lo's 2011 "Mourn" is dedicated to Hong Kong's annual mourning of the "June Fourth" event. Audio from TV broadcasts of the gatherings are excerpted and manipulated to subtly intervene with the listener's time and space at low volume.

The most outspoken political sound art work comes from Taiwan: Hwang Dawang and Zhang You-Sheng's "Minkoku Hyakunen" (100 Years of the Republic of China) is a political satire on the current Nationalist regime (which was celebrating its 100th birthday), using invasive phonography, where the artists comment and even "act" on the various scenes being recorded. The highlight of this CD is the segment where they record a military band playing the national anthem, while the artists/recordists begin their funeral wailing. The title itself, written in Japanese to show their disdain for the ruling Nationalist Chinese party, contains a pun on the word "100 years," which also means passing away, while officially it was used to commemorate the 100th national anniversary. The political use of creative phonography earned them an Honorable Mention award in Prix Ars Electronica, 2012.

"Noise is power," the French theoretician Jacques Attali would say, but, here, noise (or sound) in itself cannot be seditious or given a political reading, without the assistance of language.

"Shanzhai" (knockoffs) is the keyword of today's China. And we are bound to ask (or be asked) this question: When every conceivable brand name, trendy foreign product, or social media platform (Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, etc.) is being knocked off with an imitation clone in China, can we see the various genres of Chinese sound practices as merely "shanzhai" copies of what has happened outside?

This is an issue too big to elaborate on here, but we could look at some specific sound works that illuminate this phenomenon in an interesting way.

Wang Changcun, a sound artist with a rare sense of dry humor as well as a vast knowledge of new music, has often touched upon this issue of "shanzhai" unknowingly, and sometimes intentionally. Such is the case with his "Antechre" live performance in Shanghai, 2007 and its subsequent release in Post-Concrete's "Archival Vinyl" series. The name and content both allude to the British electronica duo Autechre, specifically their "Untilted" CD. In Wang's release, the live recording of his performance was presented misleadingly as one of the many widely circulated bootlegs on the Internet by the real band "Autechre," with accuracy down to the made-up bootleg lineage listing, the spatial quality of the recording, and scattered audience applause.

Much more ambitious is his tour de force produced and released by Post-Concrete, "Klone Concerts" (2008), which is presented as a real solo piano improvisation recital, but in reality a set of algorithmically composed pieces triggering grand piano samples. This work is not only a display of Wang's programming ability, the artist and his producer's cynical playfulness, but also a sincere homage to Keith Jarrett's "Köln Concert." Wang's release was an immediate and huge success in the experimental music circle, but not due to any of the above, rather simply because of the beauty of the music itself.

In fact, the society's total acceptance of plagiarism is so pervasive that it has reached a point where we cannot say for sure whether Wang Changcun's "Antechre" and "Klone Concerts" are intentional mocking, or subconscious imitation then dressed up as parody after the fact. Either way, it is a poignant mirroring of the much larger social phenomenon of "shanzhai."

A direction of sound practice in China worthy of special attention is one that employs the platform of the Internet, the virtual, the post-Internet smartphone, and social media. Yet beyond the surface of merely trendy and geeky sound experiments, there is a deeper characteristic shared among such works, that is, a highly reflexive look at the platform, the medium, and the element of the social itself.

As early as 2001, Fu Yu, half of the pioneer media art duo 8GG, created "Internet Soundscape," a work documenting the sound of the Internet via the Netscape web browser. Zafka (Zhang Anding) took the idea of virtual soundscape one step further with his 2007 limited edition vPods (knock-off iPods with sound tracks pre-installed) and 2008 CD release "i•MIRROR," which contains a soundscape created from sound snippets recorded in the virtual world platform Second Life (www.secondlife.com).

In the mid-2000s, Xu Cheng made extensive recordings of online chatroom conversations and other net broadcasts, covering a wide range of topics, from underground Christian sermons to S/M bondage master classes. These works dig into and open up an acoustic world inside the Internet, of life on the Internet, which is usually considered only as a carrier of sound files and sound information exchange.

Personal computer with Internet connection played a crucial role in the beginning phase of sound art in China, from retrieving information and sound works, to the production of sound, networking among artists, dissemination of works and event info, etc. As we move away from the PC and the Web in this post-Internet era, new mediums are offering new potentials.

In 1997, China Sound Unit began paying attention to the medium of cellphone and started cellphone surveillance recording in various cities in China. This project has since accumulated an archive of sounds of the society before 1999, the year when the cellular carrier system was switched from analogue to digital and surveillance became no longer possible. The archive is an important resource for sociological, historical, phonological, or psychological research. Whether this collection of "sound objects" can be called sound art is irrelevant; it certainly can be if exhibited in public or released on CD (for example, Beijing Sound Unit Archive.XX1, released on Post-Concrete in 2008).

In 2005, a few years before smartphones and iPhones became the standard in China, Jiang Zhuyun (a.k.a. Jimu) performed a unique cellphone work at the opening of "Sound Imaginations," a China Academy of Art sound art exhibition featuring works by over 20 artists, in which he had two cellphones crossed with the earpiece of one phone facing the mouthpiece of the other, and then he dialed two different numbers on the two phones. And so the spontaneous, yet totally passive, dialogues ensued, hence the title of the work, "Start with Wei" ("start with hello").

And as the iPhone landed in China, works making use of the new device, which is a convenient recorder, among other things, surfaced all over the map. Edwin Lo made a CD (Post-Concrete, 2011) of monophonic iPhone phonography recordings in Hong Kong. Vavabond's (Wei Wei) "iPhone Improvisation" (2012) is a performance in which she experiments with attaching various transducers to the body of iPhone and then performs various tasks on the iPhone body as well as on the iOS system, thus picking up a stream of unpredictable noises.

Wang Changcun also wrote and released the first Chinese sound art app for the iPhone in 2012, titled "Cicadas," in which the user can design and control his own cicada sound by changing the parameters on a series of sliders.

Dajuin Yao and his Soul Lemon band performed in Shanghai in 2010 on iPhones and iPads only. Different from other such performances, Soul Lemon improvised with only non-musical apps, such as utility and game apps, and they even handed their system to the audience, who took over the show halfway into the concert.

With the advent of social media, we see a new frontier on the horizon. In 2008, Zhang Liming (a.k.a. Hitlike) setup the "Harbin Sound Map," a web sound project in which the users can post and share their own recordings according to geographical location. The similar construction and idea were used by Zhang Liming and Wang Changcun in their 2009 collaboration "China Sound Map."

These are but two early and cruder examples of using a social media framework for the production of sound. Sound in social media, especially in more recently developed forms, are significant for several reasons. First, the structure is founded on the principle of UGC, or "user generated content," and the results are collective productions of sound. This is an important paradigm shift that brings the production rights to the formerly called "listener"; now everyone is the producer as well as the consumer. If we examine this ecology through Jacques Attali and his monumental work "Noise: the Political Economy of Music (1977), we can say that this current stage of social media can be called "Noise 2.0," and a much belated arrival of his predicted stage of "Composing," where everyone creates his own music, or noise. This is one step beyond the stealth phonography practice mentioned above – giving up the artist-oriented concept of sound art altogether. Or, if we follow the "noise is power" line of thinking, then this is a liberation from a traditional noise concert hierarchy: one noise star vs. a roomful of fans. Now, the power is in the hands of every mobile user; everyone is Buddha.

Secondly, social media sound signals a return to the pure, phenomenological aspect of the "sound object" as originally defined by Pierre Schaeffer, that is, sound "as object" in itself, not "art." With larger social media platforms (such as the new PaPa in China), the production, exchange, transfer, and consumption of "sound objects" have reached historic heights.

Dajuin Yao's "Sound Tube" (2011~) is an unusual case of using social media. Over TalkBox, an iPhone voice messaging platform from Hong Kong which became quite popular in China before being cloned and killed off by a large Chinese conglomerate, Dajuin and a friend whom he had not met started chatting in sound recordings, instead of voice. The "conversation" has continued for almost two years now and they have never spoken on the iPhone. Without doubt, the sound snippets being exchanged can be collected into a work of sound art, but it can also remain only as a long, private conversation between two persons. The key is, sound does not need to be art to be fun or gain meaning.

This brings us to the final work, PaPa. PaPa will be shown in this exhibition in the form of an interactive installation, but it really is an iOS/Android app. This new social media platform lets the user post a picture together with 90 seconds of sound. Over one million users have registered on PaPa in only four months of its existence. It is one of the most popular social media platforms in China now and still rising fast. On PaPa, you can hear people's Karaoke singing, wakeup murmuring, or the sound of the environment. With over one million participants, it is an extended form of "phonography," to say the least.

Such social platforms of sound promise to realize the largest-scale collective act of not only producing sound objects, but also the consumption of sound, or, the act of listening, in history.

Today's China is one of the most rambunctious and noisy countries in the world. Rampant noise, especially noise in public space, such as the broadcasting of non-stop background Muzak at Shanghai subway stations, on railway trains, individuals broadcasting their private cellphone conversations at high volume, etc. This different ideology of sound, one of the most negative aspects of living in China, is, ironically, also what imbues the society with inexplicable acoustic energy.

At about only ten years of age, sound art in China is still young; too young to predict its future. But one thing is certain – the sounds currently running uncontrolled in everyday life will be gradually disciplined as the country moves rapidly toward its goal of "civilizing," while what is known as "art sound" will come to flourish within its art world ecology, as sound art.

Yet, what might be most worthy of our expectations will be a different kind of sound practice, mode of listening, or acoustic energy, one that has little or nothing to do with installation, artist, or even art, one that is out of sync with the global sound art agenda. That energy is continuing its search for viable outlets and platforms. What we can do now, is to lend our ears.

A bell is struck, a wave of metallic articulations pierce through space. A ringing resonance lingers long after the abrupt percussive event, like the persistent afterimage of the camera flashlight. For a brief moment, time stands absolutely still. Dreaming takes place between an initial sounding and its infinitely extended decay.

This short essay is a meditation on the sonic dreamscapes that follow an articulation of sound. My points of departure are contemporary episodes of hearing and sounding in the age of cultural and technological convergence. They open up into brief elaborations on two important Chinese treaties on the nature of the auditory.

Normal conversations are at 60 decibels. A whisper in the ear is measured at 30 decibels, fluttering leaves at around 20. At which point does a sound escape the realm of perception and pass into the void of sonic nothingness? In neuroscience, the absolute threshold of hearing (ATH) refers to the smallest level of sonic stimulus that is detectable by human ears. This threshold is not an absolute. Instead, it is expressed as a level at which a response is registered at a certain percentage of time. The threshold of aural perception is, as it were, an aspiration. An infant’s sense of hearing is the most sensitive, but just like one’s childhood innocence the ability to decipher the finest gradations of sounds also fades with age. According to a report by the World Health Organization, hearing impairment affects more than 250 million adults around the globe. But hearing is both physical and psychological: our audible edifices may be enlarged by the will of the mind.

The educational resources website of the Institute of Acoustic Ecology details an ear-opening exercise that might help to “reverse” aural desensitization, “…pay attention to, as you might watch, a sound that travels through your listening space. Try to notice a sound just as it becomes audible, and follow it until it is barely perceptible.” Ear-opening exercises such as this assume that our field of aural perception could be expanded by an active and directed imagination. There is a performance practice of “hearing expansion” in tradition of Western classical music. Decrescendo a niente – the Italian musical instruction that literally translates “to fade to nothing,” is often realized in performance as a charged silence in the aftermath of a final sonic utterance. These brief moments right before the bath of voluminous vibrations totally recedes – when the instrumentalist and the audience collaboratively perform an imagination of the infinitesimal residuals of sound – are some of the richest and the most hauntingly beautiful moments of contemporary auditory culture.

Decrescendo a niente asks that we imagine a never-ending decay, one that is indefinitely suspended by an over-active imagination. Another performance indication cantabile, literally translate “to perform in a signing style,” demands that the player imagines impossible songs instead. Instruments of the Western classical tradition constantly aspire to the condition of the human voice. The bending of pitches, the soaring crescendo, the stylized fluctuation of frequency otherwise known as vibrato – all of these are features of the human voice that the instrumentalists seek to reproduce with their interfaces. Keyboard instruments are less capable of imitating the human voice, due to its essentially percussive nature and short sustain. For this reason the fortepiano was considered by 19th century critics such as Heinrich Heine as an “unnatural machine” inferior to string instruments. To “represent the spirit” keyboardists are trained re-imagine the “shrill clinking tones” of the piano as legato vocal lines, in an attempt to transcend the limitation of the instrument. The will fills out the spaces between articulations, and subverts the machine into a vehicle that channel the sublimity of human emotions.

Above are instances of hearing in which the mental colors, distorts, and sustains the auditory. In these moments our sense of hearing is articulated by an initial sounding, which opens up a field between sound as a physical phenomenon and as a psychological manifestation, a space that is held up by our imagination. For as long as our imagination remains active, our sense of hearing remains acutely articulated.

Composer and sound artist Susan Frykberg once referred to the moments between articulations of sound as the “auditory space between sound events.” Frykberg was actually referring to the literary metaphors of silence in her writing; and I say “metaphor” because silence in absolute terms does not exist. This scientific observation was popularized by John Cage’s lecture on his own experiences in the anechoic chamber. For as long as we live, we are accompanied by the sonic murmur of biological processes. John Cage’s silence contains non-intentional sounds. Sonic utterances come into being, degenerate, and eventually cross-fade into the barely audible sounds that the body produces. In an age that demands an intensified level of communicative nuance, the Cagean thesis of silence remains inadequate in accounting for all the poeticisms of the over-active space of sonic in-between-ness. Silence implies inaction, even suppression: R. Murray Schafer famously proposed that to appreciate silence we first “still the noise in the mind.” Never-ending decays on the other hand are moments of intense mental focus and aurally directed hyperactivity, which collapses into sonic nothingness only when our imaginations become disengaged. Here, it is useful to recycle Frykberg’s notion of the auditory space, to mark an explicit distinction between the infinitesimal residuals of sound, and the inactivity of silences. The auditory space is at once internal and external. It is an active and directed expansion of hearing, which conjures up a mental space of “limitless ecstasy of infinitude,” an act that is capable of transporting us into “realms as remote from our brutish beginning our animal present will permit.”

The auditory space between articulations was the subject of intense aesthetic contemplation and theorization of the literati class of ancient China who revered the qin (古琴 or simply 琴) – a plucked seven-string instrument. Invented some 3000 years ago, the qin once enjoyed a privileged cultural status as the highest of the “four arts of the learned scholar” (四藝). Qinsheng shiliu fa (Sixteen Rules for the Tones of the Qin) is a 13th century thesis devoted entirely to the fine art of qin playing, and is considered to be one of the cornerstones of qin aesthetics. Written by Ming dynasty (1368–1644) intellectual Leng Qian, Shiliu fa deals with every nuances of qin playing with a focus on the production of the ideal tone.

The thesis is exposed in sixteen short texts. Each is an elaboration on a Chinese character that is appropriated to encapsulate the technical, spiritual and moral ideals of qin playing. The sixteen texts fall loosely into one of four archetypes, namely: technical manuals (for instance 輕, 鬆, 脆 and 滑); stylistic statements (古, 澹); statements of a moral-philosophical nature, pertaining to the ideal character of the cultivated qin player (幽); and statements on the yi jing (意境) that a learned player of the qin should aspire to project. Yi jing is perhaps one of the most complex concepts at the core of classical Chinese aesthetics, and a full explanation of its nuances requires a book of its own; to over-simplify for the purpose of our discussion – yi is a directed imagination that resides in the mind of the creator, and jing refers to the poetic space of artistic resonance that the right mind set projects. In the passage qing (清), Leng invoked the bronze bells and sonorous stones to describe the pure quality of a good tone. It is obvious that Leng had more than the initial articulation of a tone in his ear:

Here, purity is associated with sonic vastness, as realized in the imagined resonances of mountain gorges and resounding valleys. To Leng, an ideally executed tone is one that transcends a priori perceptual categories. Each tone opens up its own sonic-psychological space, expanding the cochlea into a vast, portable, audible edifice – an auditory space of infinitude. Purity in this sense can be thought of as a spatial imagination that is unobstructed by defects in the production of tones. A perfect tone, which is capable of evoking a sense of space, is the result of a cultivated mind; the mind in turn is nourished by the experience of sonic emptiness. This interdependence of the internal (the soul) and the external (sense of space) is articulated throughout Shiliu fa. In the you (幽) section Leng writes:

“What is really difficult is to express emptiness…if the tones are serene, then the player shows that he has achieved the expression of emptiness…When the spirit of the melody is expressed, then the heart will become serene as a matter of course, and when the purity is refined, the tones shall naturally be empty.”

The fascination with a single tone and the psychological auditory space that it opens up is a concern that appears to permeate a number of important Chinese theses on the nature of the auditory, including the Yue ji (records of music). Completed prior to the Western Han dynasty, Yue ji is the earliest fully developed musical treaties in China. Contents of Yue ji are also found in a number of other important ancient Chinese texts on music. Scholar and historian Yuhwen Wang pointed out that Yue ji and the aesthetics of the qin share the same social ideal of cultivating virtuous dispositions through music. In the Confucius tradition, it is believed that sound and music has the power to shape the character of an individual, as well as the behaviors and depositions of the collective. If Yue ji is the first comprehensive account of the Confucius musical ideal, then qin playing is the theorization of Yue ji realized in practice. Much has been written about the political ideas in Yue ji, what is less discussed is its definition of sound objects, and how they function on multiple levels. Yue ji represents a unique approach in the categorization of sounds: it identifies three unique classes of sonic phenomena, namely sheng (聲), yin (音), and yue (樂). Yue is perhaps closest to our normative understanding of the term “music,” but it is more than just music: it represents an integrated art that is comprised of melodies, songs, and dances. Yin refers to sounds that are produced with an artful or musical intent, which is to say, organized sounds. Sheng is what John Cage might call “the entire field of sound,” and it refers specifically to all sounds and noises that are the result of human activities.

Yue ji must be read in close reference to the theory of mind-body unification that dominated Chinese thinking at the time. Distinct from the Cartesian separation of the body and the mind, in this line of thought physical and psychological conditions are interdependent, constantly asserting their influence on the other. At the time when Yue ji was written, this would have been an assumed knowledge of the literati class that required no elaboration. The centrality of mind-body unification is perhaps one of the most neglected aspects in the reading of Chinese treaties on the nature of the auditory. To quote Yuhwen Wang:

“While mind-body unification is acknowledged in Sinology studies, its significance has not been well recognized in the study of Chinese music. When Chinese texts are translated into English, many connotations, contexts, and nuances in the original text are lost. Among these, the assumption of mind-body unity is a particularly important one.”

According to Yue ji sound occurs simultaneously on several levels. Sound in the world of physics is expressed as frequencies and vibrations, but causally sounds are also the direct result of a certain psychological state, which either manifest externally as a sonic expression (exclamation, laugher, sigh), or internally as a frame of auditory perception. The auditory is a psychological experience that is distinct from sound as a physical phenomenon. A single sonic object can give rise to a multiplicity of auditory experiences. In this sense, there can be no sound without the mind. Sound is an interface, and a bridge into a dream world of affects, memories and imaginations:

“Music is (thus) the production of the modulations of the voice, and its source is in the affections of the mind as it is influenced by (external) things. When the mind is moved to sorrow, the sound is sharp and fading away; when it is moved to pleasure, the sound is slow and gentle; when it is moved to joy, the sound is exclamatory and soon disappears; when it is moved to anger, the sound is coarse and fierce; when it is moved to reverence, the sound is straightforward, with an indication of humility; when it is moved to love, the sound is harmonious and soft. These six peculiarities of sound are not natural; they indicate the impressions produced by (external) things.”

Andre Nusselder in his book Interface Fantasy describes a Freudian perspective of fantasy spaces, in which cyberspace is likened to a “consensual hallucination.” In this sense, the experience of the auditory space is also a sort of consensual hallucination, a sort of “sonic cybernetics,” as it were; while the Cagean silence is more likened to putting a frame around time, in a typical post-modern gesture of re-contextualization. This difference is a subtle but important one. If, following Yue ji, sonic utterances are reflections of the sensibilities of our times, then the auditory is a pathway into a world of shared memories, common culture and sensual connectedness. Scientist and the “father of computer” Charles Babbage once speculated that sounds never disappear entirely after an articulation, but are instead “archived” as imprints on the atmosphere’s particles:

On the wings of sonic emptiness, one soars above and beyond nature, escaping the ubiquitous and ever-present murmur of biological processes. Shiliu fa and Yue ji point to a superimposition of temporal structures – virtual time and linear time. Here, each articulation of sound is an interface into the world of fantasy, infinitesimal residuals, and interconnected sonic-cybernetics.

I am decidedly disinterested in replicating the notion of an “ethnographic ear,” or the self-Orientalizing assumption that the Chinese hears differently. That said, by shifting between the historic and the contemporary, the Chinese and the non-Chinese, I hope to have approached a culturally sensitive and experientially nuanced contextualization of auditory perception. It is my belief that even in the face of the contemporary sonic “schizophonia” (a terminology coined by R. Murray Schafer, to describe the post-modernist separation of sound from its social and cultural source), in discussions in which one is focusing primarily on the materiality of sounds, we could continue to speak of culture for it heightens, expands and clarifies the sensual.